While the data is still preliminary, it appears that deforestation declined across the tropics as a whole in 2023 due to developments in the Amazon, which has more than half the world’s remaining primary tropical forests.

Sharp decline in Amazon deforestation

An analysis published in December by the MAAP initiative revealed a significant decrease in deforestation. In the first 11 months of 2023, deforestation totaled 912,000 hectares, marking a 56% reduction compared to the same period in 2022, and a 68% decrease from 2020 levels.

Brazil played a key role in this decline. The country’s National Space Research Institute (INPE) reported a 22% decrease in deforestation for the year ending July 31, 2023. This downward trend intensified after August 1st.

Lula prioritizes the Amazon

A major factor in reducing deforestation across the Brazilian Amazon was the transition from Jair Bolsonaro’s administration, which dismantled environmental protections, to Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva’s. Lula campaigned on a platform of addressing rampant forest destruction.

After reassuming office on January 1, 2023, Lula swiftly began reinstating conservation programs and strengthening environmental law enforcement. He rallied international support for Amazonian projects, recognized new Indigenous territories, and took steps to respond to the Yanomami crisis. Through various statements and summits, Lula proposed an alliance among forest-rich countries to secure more funding for forest conservation and to develop regional bioeconomies.

However, Lula encountered criticism due to the decision by Brazil’s National Oil, Gas and Biofuels Agency (ANP) to auction off 602 oil and gas exploration blocks, which included 21 blocks in the Amazon. Additionally, Lula is contending with a Congress that is resistant to many of his administration’s environmental policies, reducing the likelihood that many will move forward.

Drought in the Amazon

Despite these gains against deforestation, all was not well in the Amazon. The ecosystem suffered one of the worst droughts on record. The drought dried up rivers, isolated communities, triggered wildlife die-offs, and intensified fires.

The drought is expected to further imperil the rainforest ecosystem, which is already showing signs of a long-term drying trend, exacerbated by climate change, deforestation, and damage from logging, fires, and fragmentation. A NASA study highlighted that parts of the Amazon have seen a warming of 3°C, surpassing the global average.

Drought in Indonesia

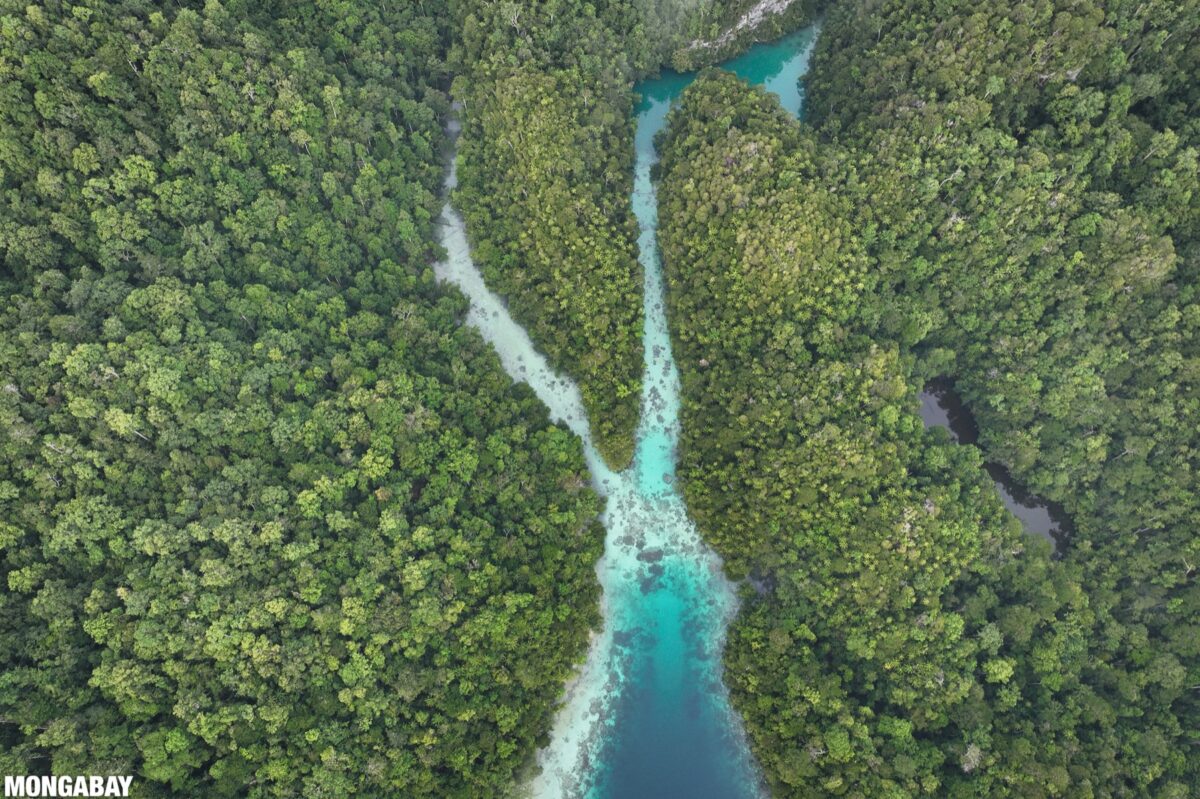

Drought wasn’t limited to the Amazon: Southeast Asia also suffered from the effects of El Niño, which suppresses rainfall in the region. Indonesia, in particular, faced widespread fires that caused air pollution and had significant health impacts. Several Indonesian companies were scrutinized for fires occurring within their concessions.

Indonesia holds the line on deforestation despite El Niño

Despite El Niño and rising prices of tropical commodities often associated with forest clearing, proxy data indicates that deforestation in Indonesia might have only slightly increased from the historically low levels recorded in 2021 and 2022.

Environmental activists and researchers have expressed concerns about several developments in Indonesia in 2023:

- There is compelling evidence suggesting that Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) and APRIL/RGE backtracked on their forest conservation commitments. An analysis by the Nusantara Atlas indicated a near fivefold increase in wood-pulp-driven deforestation from 2017 to 2022.

- Government’s restoration claims appeared to once again fell short of their promises.

- Experts cautioned that the recently-revived food estate program was repeating the errors of previous versions, such as deforestation, peatland degradation, land conflicts, and disappointing agricultural yields.

- The government granted amnesty to 237,511 hectares of oil palm plantations illegally established within forest reserves.

- Environmentalists continued to question the sustainability of Indonesia’s new capital city, currently under construction on the island of Borneo. However, government officials have dismissed these concerns.

- There were numerous instances where companies, despite having their operating permits revoked for illegal land clearing, continued operations as usual. In a notable case, a judge allowed a company to proceed with clearing 26,326 hectares of primary forest in Papua, potentially leading to the deforestation of 280,000 hectares for oil palm plantations.

With the 2024 elections approaching, observers familiar with historical trends in Indonesia fear an increase in deforestation as the vote nears. Research has shown that candidates often finance their campaigns by granting concessions to logging, mining, and plantation companies.

Regulation on imports of commodities linked to deforestation

Indonesia and Malaysia entered into negotiations with the European Union over the block’s Deforestation-Free Regulation (EUDR), which prohibits imports into the E.U. of commodities sourced by clearing forests. The EUDR, which came into force June 29, 2023, covers seven primary commodities: cattle, cocoa, coffee, palm oil, rubber, soy, and wood, as well as a range of derived products specified in the regulation’s annex, such as leather, chocolate, and pulp and paper. Indonesia and Malaysia are pushing for exemptions for some producers, including smallholders.

The U.K. government also announced a list of forest-risk commodities that will be subject to an import ban if they were sourced from illegally deforested land. However, environmentalists argue that the UK’s focus solely on the legality of deforestation renders its regulation significantly less robust than the EU’s EUDR.

In the United States, similar proposals have been introduced at state levels, but none have been enacted into law. A notable instance occurred in December, when New York’s governor vetoed the New York Tropical Deforestation-Free Procurement Act, highlighting the challenges faced in implementing such regulations in the US.

Eventful year in the forest carbon market

Forest carbon markets, anticipated as a major funding source for tropical forest conservation and restoration, experienced a tumultuous year.

After a post-pandemic boom associated with rising concern about climate change and hope that “nature-based solutions” could help solve many of the problems of our own making, the forest carbon sector endured a series of controversies in 2023. These ranged from persistent doubts over carbon accounting practices to efficacy issues, and concerns about project developers respecting Indigenous land rights and consent.

A notable Science study, which garnered significant attention, concluded that 94% of the credits generated from 26 REDD+ projects didn’t represent real reductions in carbon emissions, citing inflated baselines. However, critics of the study, including a rebuttal by prominent forest scientists, argued that these projects represented only a fraction of all REDD+ projects and highlighted what they considered major flaws in the study’s methodology.

These various issues exerted pressure on key entities in the voluntary carbon market. Verra, a leading carbon credit certifier, had to suspend projects, manage the departure of its CEO, and introduce a new, stricter accounting standard. Following an exposé in The New Yorker, South Pole, the largest carbon offset seller, severed ties with its biggest supplier, the Kariba REDD+ project in Zimbabwe, due to questions about the integrity of its credits.

The confusion over varying voluntary standards, compounded by ongoing controversies, prompted several major organizations, including Verra, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve, Winrock International’s American Carbon Registry (ACR), Architecture for REDD+ Transactions (ART), and the Global Carbon Council, to pledge to collaborate in establishing more consistent certification criteria. This commitment was echoed by several initiatives, such as the Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), Science Based Targets initiative, We Mean Business Coalition, Climate Disclosure Project, Greenhouse Gas Protocol, and The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market (ICVCM). In December, these groups agreed to develop an “end-to-end integrity framework” to provide uniform guidance on decarbonization efforts and the role of “high-quality carbon credits” in “enhancing corporate climate ambition”, as reported by Carbon Pulse. Furthermore, The Integrity Council for the Voluntary Carbon Market announced the creation of the Indigenous Peoples and Local Community’s Voluntary Carbon Market Engagement Forum to strengthen their involvement and the benefits they receive in a high-integrity voluntary carbon market.

Supply and demand for REDD+ credits appeared to be on track to decline in 2023, according to analysis by Carbon Direct. But a report from Ecosystem Marketplace suggested that prices might increase, indicating a shift towards higher quality projects.

The development of a global compliance market for carbon credits faced a significant obstacle at COP28 in Dubai, where participants failed to reach a consensus on Article 6 of the Paris Agreement, which addresses carbon trading. Many view the establishment of this market as essential, not only to boost the financial resources directed towards forest conservation and restoration but also to enhance the overall integrity of the market.

On the regulatory front, the U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC) proposed guidance in December to enhance oversight of trading in voluntary carbon credits.

Guyana, having issued the first Jurisdictional REDD+ (JREDD) credits in 2022, sold $750 million worth of credits to Hess Corporation, an oil company. Next year the Brazilian state of Tocantins is expected to verify and sell JREDD credits, potentially unleashing a wave of activity in the space.

Rainforests and Indigenous Peoples

The contribution of Indigenous peoples and local communities to the management and conservation of tropical forests has gained increasing recognition in recent years.

Several high-profile studies and reports published in 2023 bolstered the argument that acknowledging the rights of forest peoples typically leads to better outcomes for tropical forests, the ecosystem services they provide, and the wildlife they harbor. For instance:

- A World Resources Institute (WRI) report revealed that areas of the Amazon managed by Indigenous people with documented or formal land claims sequestered a net 340 million metric tons of carbon dioxide, in stark contrast to the broader Amazon, which became a net carbon emitter due to deforestation, degradation, and forest die-off.

- Research in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) Nexus found that in Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, Indigenous territories with formalized land tenure experienced lower deforestation rates and higher reforestation rates.

- An analysis by the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP) indicated that deforestation was lower in Indigenous territories than in protected areas between 2017 and 2021.

- A study in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences observed greater forest recovery in Brazilian Amazon communities with Indigenous land rights compared to adjacent areas.

- Beyond the Amazon, a study published in Nature Climate Change covering 15 tropical countries found that forests managed by Indigenous peoples and local communities are associated with improved carbon storage, biodiversity, and forest livelihoods.

Despite these findings, the financial support reaching these frontline communities remains a fraction of total conservation funding. A report examining a $1.7 billion pledge made at the 2021 U.N. climate conference to support Indigenous peoples and local communities’ land rights found that while 48% of the financing was distributed, only 2.1% went directly to Indigenous peoples and local communities.

2023 witnessed the creation of various funding mechanisms and plans by Indigenous and local groups, including initiatives like Shandia under the Global Alliance of Territorial Communities (GACT), Nusantara in Indonesia, the Mesoamerican Alliance of Peoples and Forests’ Territorial Fund, the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil (APIB) national fund, and the Central African Indigenous network’s (REPALEAC) mechanism in the Congo Basin.

However, there’s still a substantial amount of ancestral land awaiting legal recognition. According to a Rights and Resources Initiative (RRI) report, while land legally designated or owned by Indigenous, Afro-descendant, and local communities increased by 102.9 million hectares (254 million acres) from 2015 to 2020, at least 1.3 billion hectares of ancestral lands globally remain unrecognized under national laws and regulations.

Rampant Illegality

In 2023, tropical forests remained under severe threat from a surge in illegal activities, a trend that escalated during the pandemic as government focus shifted elsewhere. The UN Office on Drugs and Crime highlighted a nexus between drug trafficking, cattle ranching, illegal mining, wildlife trafficking, and land grabbing in the Amazon. This period also saw a corresponding increase in violence against environmental defenders and Indigenous peoples across many regions.

Other developments

Ecuador: Ecuadorians voted to stop all future oil extraction in Yasuní National Park, one of the most biodiverse places on Earth.

Suriname: A plan to bring Mennonite farmers to Suriname sparked fears about a potential increase in deforestation in a country with minimal forest loss.

Deforestation in DRC: Conflict and the ensuing humanitarian crisis in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo is taking a toll on Virunga National Park, which experienced a sharp rise in deforestation.

Degraded forests are quieter: Research in soundscape ecology revealed that degraded rainforests are quieter. This finding offers conservation agencies and communities a potentially reliable, low-cost method to monitor the health and recovery of tropical forests.

Deforestation correlates with drought: New studies provided further evidence that deforestation in the Amazon is linked to reduced regional rainfall, increased regional temperatures, and can affect precipitation patterns as far away as Antarctica and Tibet.

Forests’ carbon storage potential: A study published in Nature reported that forests could potentially store 226 billion metric tons of carbon if they are protected and restored, equivalent to about one-third of the excess emissions since the onset of industrialization.

Forest regeneration not keeping pace with deforestation: A study published in Nature showed that regenerating forests have only offset 26% of the carbon emissions from new tropical deforestation and forest degradation in the past three decades.

Missing the mark on forest commitments: The Forest Declaration Assessment said that a 4% rise in 2022 puts the world off track from a high-level commitment to end deforestation by 2030

COP28: The final text from the climate talks in Dubai included a call to halt deforestation by the end of the decade. But there was little progress on lining up the funding to meet that goal.

Previous year-in-reviews:

2022 | 2021 | 2020 | The 2010s | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2009