In the second half of the 20th century, animal protection was often treated in public debate as a minor cause, sentimental at best and unserious at worst. Those who pressed the issue were commonly dismissed as eccentrics or moral scolds, their concerns indulged but not absorbed.

One figure helped shift that balance by refusing to treat animals as a side issue. She did not argue from policy papers or institutional authority. She argued from outrage, persistence, and the leverage of fame, insisting that suffering without a human voice was still suffering, and that wild animals were among the most exposed of all.

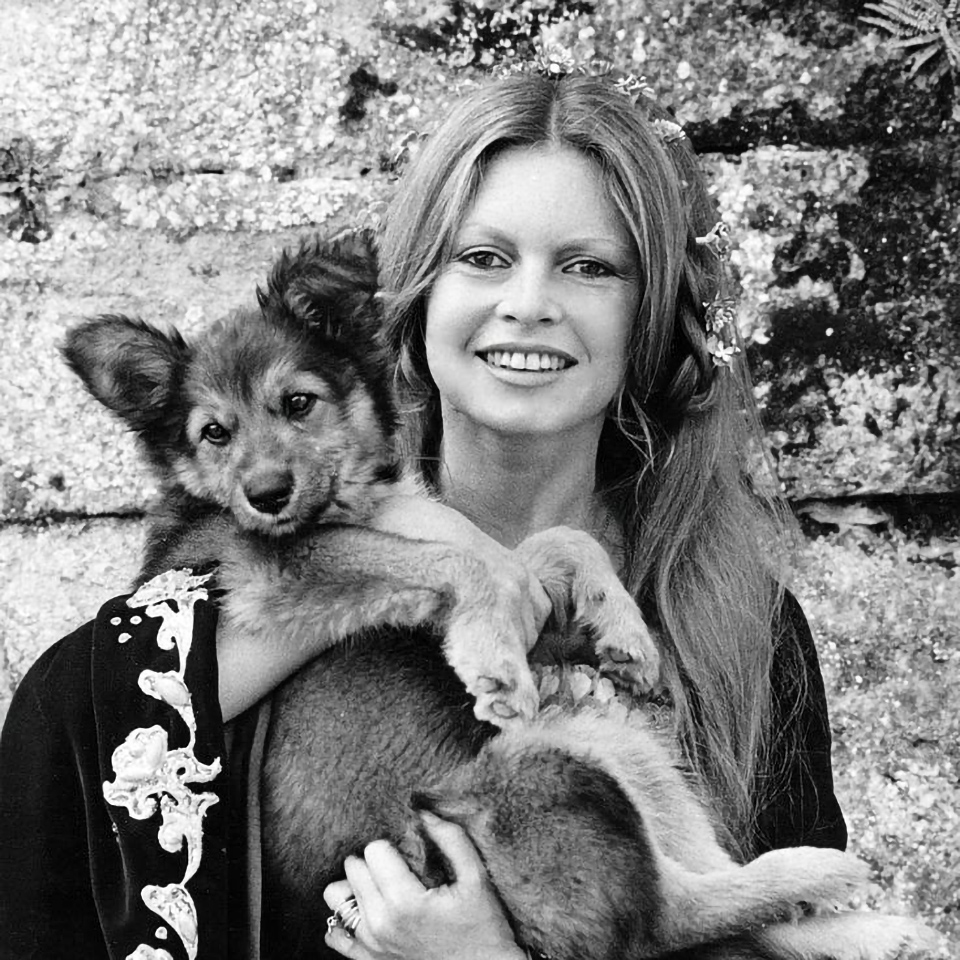

That figure was Brigitte Bardot. Known first as a film star, she abandoned cinema while still a global celebrity and redirected her public life toward animal advocacy.

Her most consequential campaigns targeted the commercial seal hunt. Bardot traveled to the ice floes of the Arctic, confronting hunters and drawing international media attention to the killing of harp seal pups. The images were arresting, but her framing was deliberately blunt. “Man is an insatiable predator,” she told the AP. The problem, as she saw it, was not a particular place or custom, but an economic system that treated wild animals as expendable material.

She extended that argument to other forms of wildlife exploitation. Bardot opposed whaling, criticized fur trapping and fur farming, and denounced bullfighting as the ritualized killing of animals for entertainment. These positions earned her political enemies and accusations of cultural arrogance. She did not soften her stance. In interviews, she often argued that tradition did not excuse cruelty, and that wild animals suffered most because they were pursued without restraint or representation.

In 1986 she formalized this work by creating the Fondation Brigitte Bardot to protect both domestic animals and wildlife. The foundation funded anti-poaching efforts, wildlife rescue and rehabilitation centers, and legal actions against illegal trafficking. It also lobbied governments and international bodies on hunting regulations and wildlife trade.

Her language remained uncompromising. “I don’t care about my past glory,” she once said. “That means nothing in the face of an animal that suffers, since it has no power, no words to defend itself.” She sometimes connected her empathy for wildlife to her own experience with relentless attention, telling journalists that she understood animals that were hunted or trapped.

Bardot’s activism was not always comfortable for its audience, and it was not designed to be. It treated wildlife protection as a moral question that could not be postponed or delegated. Long after she left the screen, she continued to insist that the treatment of wild animals was a measure of modern society’s restraint. The argument did not depend on consensus, only on repetition and refusal to step aside.

Bardot died on December 28th, aged 91.

The full length version of this obituary is available on Mongabay: Brigitte Bardot, who turned fame into a lifelong fight for animals.