In the steaming lowlands of Veracruz and the Yucatán, where strangler figs knot the canopy and howler monkeys bellow at dawn, a slight man with a field notebook kept noticing what others overlooked. Arturo Gómez-Pompa believed tropical forests were not untouched wilderness but “landscapes of memory,” shaped for millennia by Indigenous hands. Long before “biodiversity” became a rallying cry, he documented how local communities enriched and tended the jungle, and argued that conservation should do the same. Few scientists did more to upend the idea of the rainforest as a pristine museum and recast it as a living archive of stewardship.

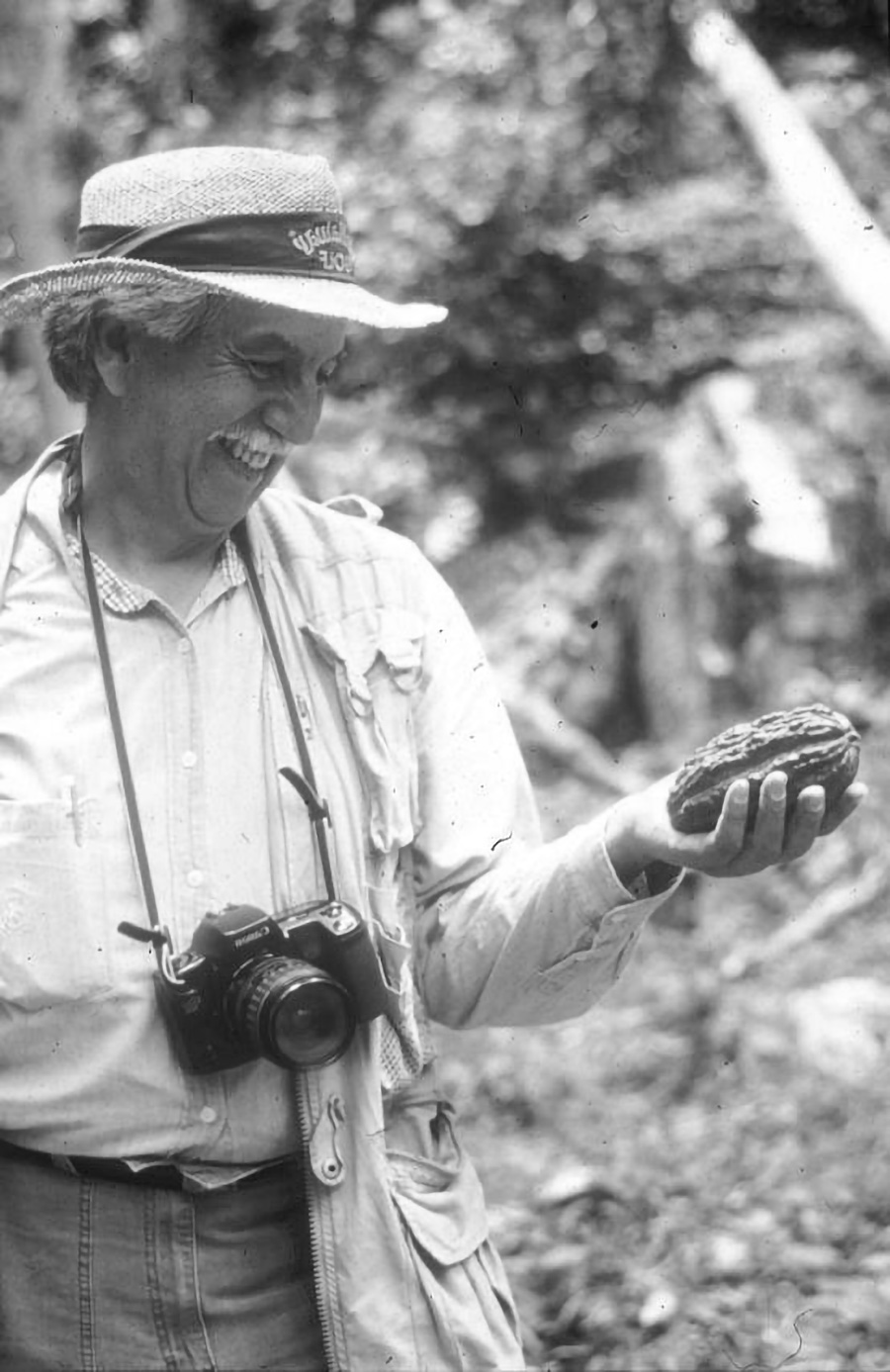

He had not meant to be a botanist. Born in Mexico City in 1934, he dutifully enrolled in medicine, his parents’ wish, until a teenage visit to a cousin’s ranch in Tamaulipas altered his course. Coyotes, rattlesnakes and hawks proved more compelling than anatomy texts. He switched to biology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), where he completed his doctorate in 1966. By then he was already a familiar figure in the selvas, cataloguing barbasco yams for a state pharmaceutical firm and learning from local guides whose names he later insisted on including in his papers.

From those muddy trails grew a career devoted to bridging science and society. In 1975 he founded Mexico’s National Institute for Research on Biotic Resources (INIREB) in Xalapa, one of the first efforts to decentralize biological research from the capital. There he helped establish agroecology as a discipline, showing that traditional farming systems often proved more resilient than imported ones. His once-dismissed hypothesis that much of the Mayan forest was semi-domesticated has since become orthodoxy.

Institutional closures did not slow him. In the 1980s he moved to the University of California, Riverside, where he rose to the rare rank of University Professor and Distinguished Professor of Botany. From there he built cross-border programs such as UC MEXUS and returned repeatedly to the Yucatán, eventually creating the privately financed El Edén Ecological Reserve when public support faltered. Today it is one of the best-studied tracts of lowland forest in the region.

His influence extended far beyond academia. He advised the U.S. House Committee on Science, Space and Technology and chaired UNESCO’s Man and the Biosphere program. He sat on the boards of the Nature Conservancy, WWF and the International Union for Conservation of Nature. More than 200 publications and a shelf of medals—the Tyler Prize for Environmental Achievement, the Chevron Conservation Medal, the David Fairchild Medal—marked his professional stature. Yet his former students, now scattered through universities and NGOs, tend to cite something else: his insistence that ecology without communities is incomplete.

He married Norma Barrero in 1958; they had three sons—Arturo Eugenio, Eduardo and Gerardo—as well as grandchildren and great-grandchildren. His memoir, Mi vida en las selvas tropicales, published in 2021, captured seven decades of fieldwork and institution-building. In its pages he wrote not of pristine jungles but of “landscapes of memory” where people and nature co-evolve. That perspective, once radical, is now a cornerstone of tropical conservation—a legacy as enduring as the forests he helped to defend.